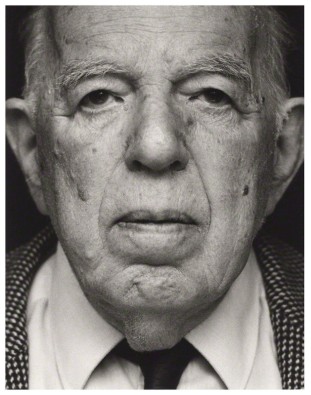

by Carolyn Djanogly, bromide fibre print, 3 May 1997

The Story of Art’, by Ernst Hans Gombrich, originally written in 1950, is a history of art from cave paintings to modern art. The chapter on which this essay is focusing, Permanent Revolution- The nineteenth century, explores the changing art scene, during the period, claiming it to be a seminal moment in art history, permanently changing the way we view and create art. This essay will explore and evaluate Gombrich’s argument, with regard to differing historical approaches and concepts. Gombrich uses artists as a framework for the turbulent period of art in the nineteenth century; he explores the idea of the era being revolutionary and lays focus on the Impressionists.

How he begins

Gombrich starts by setting the era into its historical context, discussing the impact of the Industrial Revolution claiming it to have destroyed “the very traditions of solid craftsmanship” and in turn paving a new way for art, one that was less focused on skill and more focused on expressing the artists’ individual personality. This contextualisation, however, becomes very sparse further on in the text; the only explanation for the period is with regard to the society of the time. Here we see a downfall in Gombrich’s analysis, by having such little focus on context it makes the era seem like it has no influence in the art of the time. Despite this lack of historical context, Gombrich does comment on the impact of the introduction of photography claiming that realism was no longer as sought after as much as emotion and individuality of style.

Revolution?

Gombrich uses the term revolution throughout the text, and as a way of heading the whole content of the chapter. A revolution means a sudden or rapid change, often regarding the over throwing of governments. Here the governmental system is the established traditionalism in art. The cyclical explanation of progress is one followed by other progress historians like, for example, Giorgio Vasari. Vasari saw art in the thirteenth century and onwards, as having three stages; from rebirth in the ancient period, to building in accuracy and then surpassing the beauty of nature and in time reaching a height of perfection, which is an anachronistic view. Similarly, Gombrich claims the revolution of the nineteenth century to have three stages, the first being imagination over draughtsmanship, secondly challenging the conventions of subject matter and thirdly rethinking the representation of men or objects in a less artificial way. Gombrich claims the revolution to have stages, undermining the meaning of a sudden rapid change, and perhaps alluding to the Impressionist approach being the correct form of art, as it grows and becomes more refined and perfected.

A teleological, ignorant view?

Gombrich prioritises Impressionism over Realism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this could be due to the period in which he is writing. In the 1950s Modernism made the idea that primitive form and the ousting of significant form was more popular, something which was first begun by the Impressionists and their focus on colour and tone. It could be argued therefore that the extract has an element of a teleological view, by knowing how art progressed into modernism; Gombrich pin points the Impressionists as important when during their time they were severely mocked, as stated in the extract, by the reception of the Impressionist exhibition: “I have seen people rock with laughter in front of these pictures”. By simplifying a period in to these steps Gombrich is detracting and ignoring other art forms and areas in the period for example: Cezanne. This focus on the Impressionists, however, could be a way of showing a simple path of history for the uninitiated reader to be able to follow a linear, story in art.

Despite the book being an overview of the changing aspects of art in history, the influences of some artists is ignored, therefore making the revolution in art, during the nineteenth century, seem solely a product of France and “a handful of lonely men”for example Manet, Monet and Renoir. Gombrich’s use of canon creates a blatant gender discrimination to Gombrich’s approach, women are not mentioned during the chapter, apart from when describing the group of Impressionists: “Five or six lunatics, among them a woman” the mocking tone of the quote, from what Gombrich claims to be a “humorous weekly”, shows Gombrich’s sheer disinterest in female artists of the period and from art in general. Gombrich, it could be argued, is following what feminist historian Linda Nochlin claims to be a typical ideological approach to art history, ignoring the “successful, if not great, women artists throughout history”. Gombrich’s approach is very much a Whig history and shows another weakness in Gombrich’s argument, by creating an overview and a simplified explanation of art, during the period; it becomes sparsely detailed and has to prioritise certain points in history. Gombrich focuses on the interesting points in art history for the nineteenth century, which could be a way of making art history accessible for the audience of the text, the uninitiated but interested reader. Gombrich is therefore making value judgements and narrowing the historical explanation, creating a weak explanation, again maybe to help his audience.

Is he just carving a narrative for the sake of the reader?

Despite his ignorance to female artists, the artists Gombrich does mention create an identity for the reader to relate to, something that would otherwise be an anonymous art movement comes to life with actual characters. The hardship of the Impressionists is described in relation to the critics and the fight against societies’ ideological traditionalism during the period, making the information seem more accessible and easy to engage with. Much like Vasari’s description of Cimabue and Giotto, although supported by diary entries, Gombrich seems to add an element of conjecture to animate the history, perhaps creating a story-like quality to the piece. Gombrich however does not focus on an innate genius, unlike Vasari. Gombrich uses mainly primary sources from quotes of people in the era and uses the paintings as the sources like Vasari. Vasari did not have the benefit of secondary sources so it could be argued that his lacking of other historical opinions is understandable. Gombrich however is, in his argument and discussion, ignoring the views of other historians, this is a distinct weakness in his chapter, and makes his information seem ill informed and one sided. Gombrich discusses actual techniques of artists, and how they have advanced through the period, linking this to a change in ideology towards a firm belief in an artist’s conscience rather than pleasing an audience.

Influences on art

Despite Gombrich laying more focus on the Impressionists he does however describe how style serves each artistic medium differently, as a way of explaining buildings in architecture, as they had distinct bygone styles. In paintings or sculpture conventions like this were not present, but he does claim that this left an uncertainty for artists and described a turbulent relationship with the public. The artists having a wider field of taste meant it was less likely to coincide with that of the public’s therefore showing society to have a direct impact with the success of an artist.

Marcia Pointon similarly talks about the economic influence of art and how artists need, what today would be called, a unique selling point, like the Impressionists challenging the zeitgeist creating their own forms of expression. Patrons were important in showing the level of an artist, Gombrich similarly rests on the importance of patrons saying that they served as a way of supporting artists but with the break of tradition came the break of this safety net. This change of period came because of the emergence of a consumerist middle class and contempt for conventions.

During post war Britain, Gombrich would have been aware of the importance in restoring culture and protecting Art. The historian Francis Haskell, in ‘Past and Present in Art and Taste’, claims that we are a product of our time, that art has many meanings to each era looking at them, but this history of taste is ignored as ‘The Story of Art’ is simply an informative text on the progression of art through history. The end of the extract shows no clear conclusion; the aesthetic movement is alluded to at the end of the chapter, perhaps showing the topic of the next chapter. Due to the nature of the book as a whole, judgements of specific time periods cannot be made fully. Thus points in history that lead to the next movement need to be focused on to help inform the reader on the pathway already created in history. By always passing onto the next chapter and the next era of history, the end of one chapter needs to link to the next, therefore a coherent, balanced, conclusion cannot be made. How can a conclusion be brought in a book, in which, by its very nature will always be expanding as art itself is an ever increasing form of expression?