Introduction.

There arises a great intimacy between an artist and his sitter. To be able to create a recognisable likeness of an individual the two must be in one another’s company for many days and the artist must study closely each little idiosyncrasy of their muse. To be a successfully captivating portrait the artist should bring out the sitter’s character or spirit, and not simply their physical likeness. Artist and sitter accommodate each other as they strive to reach common ground. Richard Wendorf claims that the actual sittings and the final portrait is a symbol of the contractual basis of the agreement between the two; the painting is a record of this transaction and a record of the personal and artistic encounter that produced it. Some portraits however do not depict the sitter themselves instead the sitter is simply a model, a conduit for the artists’ idealised presentation of a character, and this is true for several of the paintings that will be discussed here. Portraiture, as Joanna Woodall states, has been the most popular genre of painting in western art and this could be due to the relatability of human features and their ability to communicate intense emotions, for this to be done successfully it relies heavily on the relationship between artist and sitter.

Fredrick Sandys (although a highly gifted artist) has been somewhat overlooked in his position in history, not regarded as part of the Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood of the original seven artists, one would assume him to be an inferior artist; his skill however is evident in his works.

By delving into the relationship between artist and subject the viewer can become more enlightened and aware as to why the portrait exists and perhaps what the portrait is meaning to convey. The literature that exists already with regard to Sandys is sparse; he is simply an additional after-thought or comparison to other more acclaimed artists in the Pre Raphaelite-movement. Sandys’ subject matters, although far from ground breaking during the period he was working, (Greek mythology, literary figures, members of the aristocracy) are presented in such finite detail his mastery of the paint should be recognised and appreciated. One of Sandys’ early patrons was Reverend James Bulwer, From 1845 to 1858 Sandys made 220 watercoloured architectural and antiquarian drawings and also etched them for Bulwer. The ability to recreate objects and buildings in minute detail would come to greatly inform Sandys’ style.

Sandys and Howell: The Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell (1882)

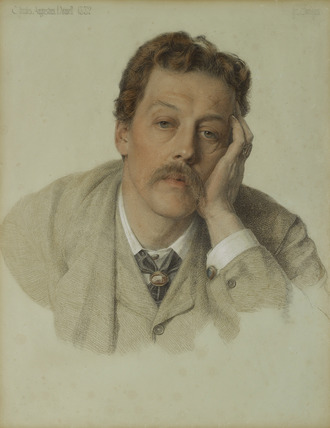

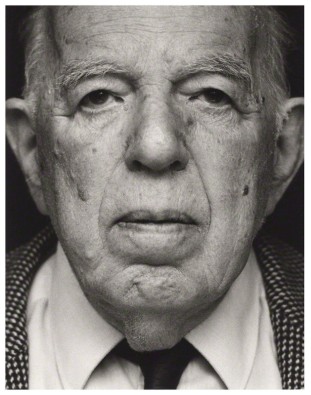

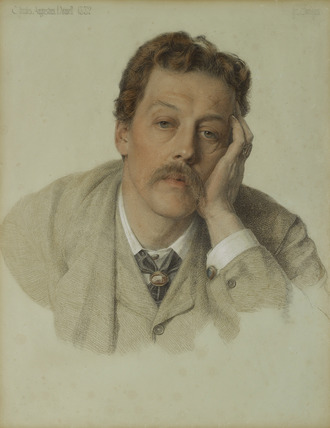

From his portrait Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell (Fig.3) Howell may seem quite an unlikely character to be a part of the inner circle of the Pre-Raphaelites: a stuffy, lethargic, formal man. Howell was however well accepted by the group for a long period partially due to his upbringing and also because of his experiences of what became his new profession. Howell did however fall from grace with accusations of theft and deception, and before this portrait he had become unpopular in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Charles Howell was the son of a British drawing master and so Howell had some understanding of art from his father and in turn he was able to better appreciate the art world, from an artist’s perspective. He became known by the Rossetti brothers; they met in 1857 and because of his appreciation of the aesthetic world and his taste in art he became closer to the Pre-Raphaelites and the art movement during the period. Sandys also made Rossetti’s acquaintance in 1857, and this could go to explain why he was also seen as an outsider in Pre-Raphaelite circles by not being at the formation of the ideals but instead just as an artist with a similar style.

From his portrait Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell (Fig.3) Howell may seem quite an unlikely character to be a part of the inner circle of the Pre-Raphaelites: a stuffy, lethargic, formal man. Howell was however well accepted by the group for a long period partially due to his upbringing and also because of his experiences of what became his new profession. Howell did however fall from grace with accusations of theft and deception, and before this portrait he had become unpopular in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Charles Howell was the son of a British drawing master and so Howell had some understanding of art from his father and in turn he was able to better appreciate the art world, from an artist’s perspective. He became known by the Rossetti brothers; they met in 1857 and because of his appreciation of the aesthetic world and his taste in art he became closer to the Pre-Raphaelites and the art movement during the period. Sandys also made Rossetti’s acquaintance in 1857, and this could go to explain why he was also seen as an outsider in Pre-Raphaelite circles by not being at the formation of the ideals but instead just as an artist with a similar style.

The meeting of Sandys and Howell.

Howell was employed to carry out Ruskin’s philanthropies and assist in setting up protégés, for example like Edward Burne Jones and Charles Fairfax Murray. With this employment therefore Howell became to have a close connection with the art world and the artists within it, further developing his taste and understanding. It could be argued by seeing the work and effort that goes into becoming technically good and understanding the tempestuous nature of the art market itself he could sympathise with the struggles artists had to go through, for example in Frederick Sandys. Sandys drew portraits of Charles Howell, his wife Kate and his daughter Rosalind. The first mention of Sandys and Howell as acquaintances is in the mention of the fact they were betting companions. A fitting introduction as Howell’s and Sandys’ relationship would come to very much rely on finance and the economic woes of Sandys himself. There is evidence of the Sandys’ Howell friendship during this time in the diaries of George Boyce, as they visited Rossetti together, the relationship was primarily economic and in turn this would lead to the demise of their relationship.

The portrait

Howell’s expression in the portrait expresses a feeling of deep tedium this could be seen to not only relate to the previously mentioned tiresome practise of sitting for a portrait but the fraught relationship of Sandys and Howell during this period. The unfinished painterly technique adds further to the intimacy of this portrait, instead of a well-polished completed portrait, it simply begins to fade away into the canvas. Much like Howell’s posture, what would usually have been a gentile pose in classic portraits it has become slumped. The colours used in the portrait also express the dull qualities of the moment being depicted and is reinforced through Howell’s expression, the pallet of beiges and the dominant white of the canvas add to the feeling of boredom. Howell seems to be floating, removed from any reality and not grounded with any background adding to the hopeless expression in the portrait.

Their relationship

Sandys’ depended on Howell to sell his pictures, help pay debts but also to find fabrics, furnishing and accessories to use in his pictures. Howell therefore had a very important role and influence in the work of Sandys by changing the aesthetics of his work and deciding what would be featured, although composition would obviously be determined by Sandys content was very much influenced by Howell’s understanding and connections. Traditional interpretations of the PRB’s state that their intention was to paint closer to nature with empirical realism and iconographic meaning. Codell perpetuates the idea that through the inspiration of the poet Keats they also constructed a symbolic language to convey tensions between social demands represented by rich material settings and intense interior emotional states expressed through body language. Here Sandys’ style can be seen to be evident, Sandys relied heavily on a dense and vivid use of colour and technique to help express varying textures seen in the clothing and hair.

From this portrait one is unable to see the other side to Howell, he was a shady character who began to become unfavoured in the Pre-Raphaelite circles as it became known of his exhumation of Elizabeth Siddal corpse, one of Rossetti’s great loves. Rossetti requested Howell to retrieve his poems that he had buried with Siddal telling Howell:

“[it] is bound in rough grey calf and has, I am almost sure, red edges to the leaves. This will distinguish it from the bible, also there”

Such an abhorrent act left Howell’s position in the Pre-Raphaelite circles weakened Howell was seen as more of an opportunist and dealer rather than a friend of the artists, and their respective families. During the time this portrait was painted therefore Howell would have been an outcast of the Pre-Raphaelites his boredom therefore could be read as sadness or a sort of apathy.

Their relationship is interesting as the painting came about as a payment for services, rather than a fete of inspiration for Sandys, or an exploration into a story or idea, it was a transactional creation that may explain the expression of Howell. The monotony of a task is represented rather than a great celebration or representation of an exciting story. The use of such a sparse background also encourages the feeling of the painting as transactional in the other portraits that will be discussed they typically have richly decorated and vividly detailed depictions of objects, objects that would ordinarily have been acquired by Howell himself, it is therefore odd that these were not shown in his portrait as he was also known to supply for other artists, such as Rossetti.

Not only was their relationship financial however but it was also personal Howell helped reconcile the friendship between Sandys’ and Rossetti, and so a genuine care beyond financial gains was also apparent. The Howell family looked after Mary Emma Jones (Miss Clive) Sandys’ lover who will be described in further detail later in the study (as she features in one of the portraits this work will analyse) and Sandys’ stayed at their residence to nurse her so a close bond was evident. This close connection could therefore explain why such an effort has gone into the portrait to create a realistic likeness, if the painting were just a plain transactional necessity the minute detail used may not have been apparent.

The portrait of Howell can be seen as extremely informal, the aristocratic character himself would ordinarily be depicted in a grand stance and setting to help describe his status and place in the social hierarchy, it is obvious in the portrait that Howell is coming from a place of wealth by his dress. It is interesting therefore to note the relationship between Howell and the bohemian world of artists, it could have lead him to shy away from his wealth especially as his sincerity in his relationships with the artists came into question prior to this portrait.

The feeling of informality is further added by the titling of the portrait and date in the top left corner of the canvas, although the text is in a classical script the use of such inscriptions was not often used, a signature would often be included but not the sitter’s name. The painting is also unusual as with most Pre-Raphaelite paintings with the figure looking out of the canvas the figure has more of an arresting look.

Sandys and Keomi. Medea (1868)

Another sitter for Frederick Sandys was Keomi Gray (sometimes referred to as Kaomi and originally named Keytamus), she was a gyspy woman that he had met in a gypsy camp in Rome. In time she became a mistress of Sandys, and popular throughout the Pre-Raphaelite circle; not only being used by Sandys but also by Rossetti

Rossetti seemed to find Keomi amusing even at questionable times he writes: “As Kiomi said when asked why she stoned a raven to death: ‘to amuse the mind’” Such an aggressive action would have seemed unbefitting for a lady during this period and could explain the Pre-Raphaelites attraction to her, beyond her mysteriousness appearance caused by her gypsy heritage.

Keomi is said to have had many children by Sandys; Ethel, Frederick Cyril, Madeline Mabel, Herbert (according to the Gorleston Cemetery records.) Sandys and Keomi therefore had a very intimate relationship that has had rather little documentation of, although they were known to have spent a lot of time together the children have somewhat melted into obscurity. This anonymity could perhaps be because Sandys was married at the age of 27 to the even more sparsely documented Georgiana Creed. Sandys never divorced her, despite the marriage breaking up after three years and he instead abandoned her. The knowledge of the children by Keomi could have caused scandal greater than having a mistress, as Sandys was married and strict Victorian morals forbade such actions.

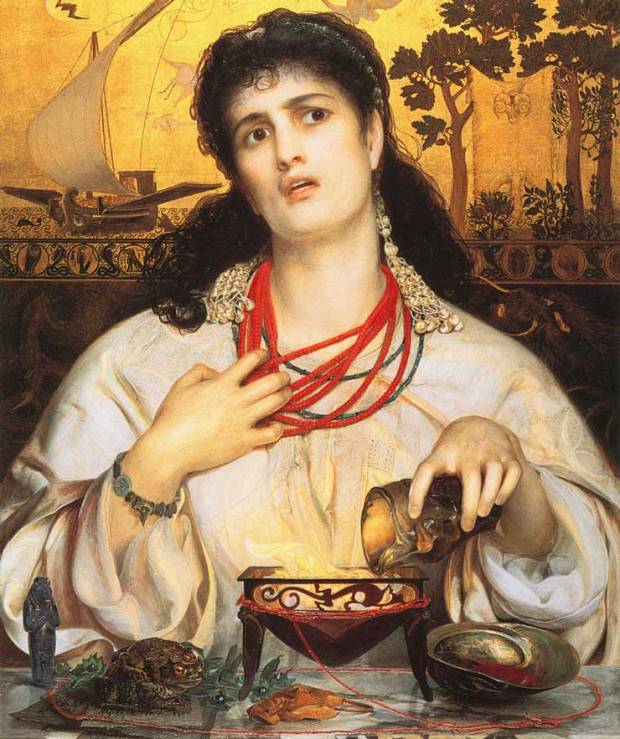

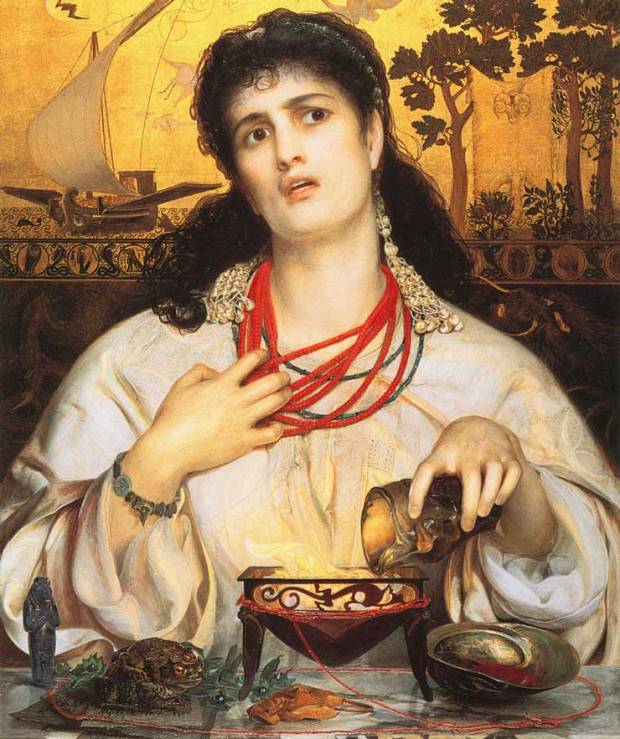

One of the paintings in which Keomi is featured is Medea. Carolyne Larrington states Keomi was a model for many of Sandys’ works and she is also featured in Morgan le Fay. Medea like Morgan le Fay is beauty distorted by passion and made ghastly by despair. Painting in 1868 and using oil on canvas Sandys creates a dramatic piece of work, not only in the staging of the work but how the character is depicted.

Medea is a figure from Greek Mythology, she was an enchantress with the gift of prophecy who helped Jason leader of the Argonauts with her magic abilities. Sandys’ Medea was accepted for the Royal Academy in 1868 but was not exhibited, which brought storms of protests from the art world of the time.

Their relationship and its influence.

The relationship between sitter and Sandys is shown in the successful telling of the story through Keomi’s (Medea’s) expression, Medea seems gripped in thought as she uses her various potions to do her bidding. The dramatic light of the glowing heat emanating from her magical mixture creates an intense focus upon the expression of Medea and her facial features, her face looks pale compared to her thick dark hair and the rich luxurious golden artwork behind her. Medea is clutching towards her throat adding a more horrifying, morbid feel to the painting akin to the worried expression. The uncomfortable atmosphere is further emphasised by the objects surrounding Keomi, with such a restricted viewpoint each object is deliberate and necessary. A shell containing a mysterious liquid for the incantation, gruesome copulating toads and Egyptian artefacts adorn the table around Medea, (although relevant to the Myth) they are an allusion to Keomi’s heritage which would be viewed as exotic and mysterious to the people of the time. Oriental dragons and Japanese cranes also feature in the painting such symbols would further emphasise the exotic qualities of Medea.

The close relationship between Keomi and Sandys can also be seen in the intense sexuality of the piece, Medea clutches at her clothes grazing her breast perhaps the irony of the other interpretations of the term enchantress (a seductress) is not lost as Keomi and Sandys clearly had an amorous relationship, especially if their rumoured children are to be true. Despite her sexuality being a focus of the painting this is juxtaposed by the uncomfortable feeling of dread. Medea although clutching at her breast is also clutching at a red, coral necklace, reminiscent of blood and perhaps creating connotations to a beheading. With the representations of such contrasting emotions (female sexuality and power) the painting therefore embodies the Pre-Raphaelite idea of the ‘femme fatales’.

The way in which Medea is framed also adds to the heady decadence of the piece a tight claustrophobic feeling is presented by the cropping of Medea’s elbows and the background being close behind. This close depiction of Medea, represents the dichotomy of female sexuality and ethereal soulfulness the figure is inaccessible and solitary and could be described as an erotic altarpiece as the singular figure in rich colours has a feeling of idolatry.

There was said to be an obsession which became favoured in art and literature for some in Late Victorian Britain with the transience of human life, due to epidemics from industrialisation such as tuberculosis and venereal disease. Such an atmosphere of mortality amongst the young lead to differing explanations, one being the previously mentioned ‘femme fatale’, which can be seen in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites and the works of Sandys. The ‘femme fatales’ were women unlike the meek domestic women Victorian values cherished, but instead they aroused a curiosity about themselves as they schemed and reaped the benefit of the men they manipulated then cast aside. [3] Eleanor Woods states Sandys was a fearless portrayer of the more malignant aspects of womanhood and it would seem Sandys liked to explore such women that were outside of his middle-class circles as he became involved with Keomi whilst engaged to the actress Mary Emma, otherwise known as Miss Clive.

Sandys and Miss Clive (Mary Emma Jones): Love’s Shadow (1867) and Proud Maisie (1864-1904).

Mary Emma Jones (her stage name was Miss Clive) was Sandys’ great love, despite having a period in which he was bewitched by Keomi, Jones was Sandys’ main object affection until his death in 1904. They had ten children together (beating Keomi’s alleged four) although Keomi could be seen as an embodiment of the ‘femme fatales’ Jones’ beauty epitomised the style of the Pre-Raphaelites. Sandys was fascinated by Jones’ thick hair, as seen in Proud Maisie (Fig.12) as she bites at a curl, just one of thirteen separate drawings that were created of a similar design from 1864 till his death in 1904. Their close relationship is shown therefore in the wealth of work created by Sandys and inspired by Jones. The painting of a similar style is Love’s Shadow (Fig.13) the two depictions are so close however that it is fair to assume the character is the same in each. The painting depicts a stubborn and angry looking young woman Proud Maisie biting on a small bunch of delicate flowers, rather than her hair seen in the drawings. Proud Maisie is a poem by Sir Walter Scott, written in 1818 the poem tells the story of Proud Maisie who is told that she is to die before she is able to find her husband, something that Victorian society encouraged women to hunt for.

“Tell me, thou bonny bird,

When shall I marry me? –

“When six braw gentlemen”

Kirkwood shall carry ye”

There was a close link between the Pre-Raphaelite movement and literature. Rossetti was a poet but also a visual artist his work as a writer greatly influenced his work as an artist. For example the previously mentioned The Girlhood of Mary Virgin was accompanied by two sonnets. The rhythm of the poem Proud Maisie is reminiscent of a death toll that emphasises the overarching theme of the poem, “Proud Maisie’s” ultimate, oncoming demise. The description of Maisie as “proud” can be seen as a way of showing her beauty, Sandys is therefore showing the aftermath of Maisie’s encounter with the “bonny bird” her frustration can be seen in her actions. Usually a symbol of classic femininity the biting of the flowers could also represent the context of which the painting was set (the forest).

During the period there was a burgeoning of feminism and so it was a time in which the traditional notions of femininity and feminine identity were challenged. Sandys could therefore be using the Maisie from the poem and putting her into his own context. Maisie would be angered by her lack of suitors and in realising that her following of the tight Victorian societal traditions has been worthless, knowing that she would no longer be able to reap the reward of her hard work, she would become angered. The painting could also be a warning to women of the period showing the troubles of staying confined to the gender traditions. In the poem beauty is personified in a woman, with focus again upon her hair and clothing. Galia Ofek theorises that hair in the Victorian era evoked a strong sense of femininity and a clear construction of gender during the Victorian period. Hair could also be used to show sexuality, Swinburne wrote of Love’s Shadow in Royal Academy Notes “biting it with hard bright teeth, which add something of a tiger’s charm to the sleepy and crouching passion of her fair face.” Sandys was not simply influenced by the social aspects of the Pre-Raphaelites he was also influenced by the techniques of the Pre-Raphaelites Rossetti was also creating Lady Lilith(Fig.14) in which Adam’s first wife is seen combing her luxuriant hair.

Sandys does however work outside of Pre-Raphaelite conventions. In Love’s Shadow Sandys has (like in his portrait of Howell) used a stark background of just one colour, however there is some detailing of leaves in the bottom right-hand corner, maybe alluding to Maisie’s setting in the poem. By using such a plain almost oppressive background the actions of Maisie are emphasised, she seems out of place clearly wearing the trappings of Victorian England to be removed and left in a dark space such as in the painting makes the viewer ponder on what has caused such heartache and exile. This unanswered question is further intrigued by Maisie’s pensive look. The viewer is drawn to the eye by the intense blue used that is intensified by the violet and blue flowers in the bouquet. The successful realistic depiction of the flowers also shows Sandys training as a draughtsman and his ability when having to represent objects with a sense of realism. The colours used are of quite a subdued palette no vibrant yellows are used, instead the painting is dominated by her luxurious red hair, cascading from the centre of the canvas, down the right-hand side and again through the centre. The eye travels in a way that frames the face. It is also interesting to note the staging of the piece, Maisie does not face the viewer, looking out of the canvas, instead we seem to be catching her in a moment of personal contemplation his is reminiscent of Italian Renaissance portraiture, and is fitting for the story of the poem.

It is shown through the many previous drawings of Maisie that she was original biting on her hair, this gives the piece more of an aggressive atmosphere and slightly

manic feel. Maisie becomes more sexualised and as a result less innocent contrasting with her physical appearance in the trappings of a chaste maiden. Less emphasis is brought upon the expression in these drawing however as her face is lost in the upper right-hand corner (rather than the centre of the painting) and is overshadowed by showing more of her body and the mane of hair. The hair itself is masterfully created with thick dry brush strokes and a slightly raised surface creating the texture of fine strands of hair.

Here we can see Sandys’ move away from the formalities of other Pre-Raphaelite works. There was a Pre-Raphaelite pastime of deep adoration for women’s beauty as, (much like the hedonistic Aesthetics movement during the period) the PRB wanted to make the world more beautiful, Rossetti defined the ideal woman of such beliefs: “This is the Lady Beauty, …By flying hair and fluttering hem”the focus upon the appearance of women is clear. Instead Maisie is presented as a powerful figure with an anger behind her beauty (as seen in Medea) Love’s Shadow and his work with Mary Emma Jones therefore represents Sandys’ unique approach to the depiction of women showing what would have been seen in the period as a juxtaposition of female and male gender traditions; beauty and aggression. Sandys was clearly deeply inspired by Jones and this can be seen in the wealth of work created inspired by her and their relationship having allowed such close adoration.

Conclusion.

As this study into Frederick Sandys shows the atmosphere of the Victorian period lent itself to scholarly and academic communication and trade, this also transferred into the world of the arts. Not only were their subject matters and sitters shared, but the style used in their depiction. The Pre-Raphaelites were a thematic and philosophic clique whose ideals and new outlook in art was ground breaking for the period. Frederick Sandys although not seen as an elite in the circle was, as explored in this study, skilfully incomparable as a draughtsman and unfairly ignored by history.

Sandys’ personal life (with regard to his relationship with women) was also as exciting as his paintings, after his ill-fated marriage to Georgiana Creed he had relationships with two women which have been explored in this study – the actress Mary Emma Jones and the mysterious gypsy Keomi. Sandys was with Keomi for five years Mary Emma (Miss Clive) however remained with Sandys for her entire life. Such relations seem to be quite a theme in the Pre-Raphaelite circles. John Everett Millais, famed with such works as Ophelia and The Bridesmaid, despite moving away from the Pre-Raphaelite style, Millais kept the ambitions of a Pre-Raphaelite by having an affair with Ruskin’s wife, Effie which began whilst on holiday with the couple.

Rossetti had an endless obsession with his models, including Jane Burden, who became wife of his friend William Morris “Janey” as she was known in the Pre-Raphaelite circle was a cult in her own right:

“…an apparition of fearful and wonderful intensity. It’s hard to say whether she’s a grand synthesis of all Pre-Raphaelite pictures ever made – or they a “keen analysis” of her – whether she’s an original or a copy. ”

Rossetti also had a tragic relationship with Elizabeth Siddal, they met in 1850 and she was the inspiration for his sonnets and romantic love, and the model for the series of drawings he made of her although never formally engaged she did visit his rooms frequently.

Looking at these instances then one might assume that a close relationship between sitter and artist is purely a Pre-Raphaelite affair, especially with their intense focus upon feminine identity and the beauty of their muses in the work. A passionate affair based on appearance however is often seen between subject and model throughout history, due to the very nature of their reason for meeting: the aesthetic qualities of the model. It could be argued this sort of visceral relationship lends itself to Pre-Raphaelite ideals but more modern artists such as Pablo Picasso and Lucian Freud are said to have had such close relations too.

In Picasso’s Fernande series his relationship with Fernande Olivier had a bearing on the way in which she was portrayed with a strong focus on her femininity and sexuality Lucian Freud however wanted his portraits to be ‘of’ people, not ‘like’ them, he is known to have had multiple children and grandchildren with different partners which John and Erica Middleton claim to be because of the power relationships between artist and model.

Not only does portraiture depict the sitter but some see portraits as a reflection of the artist himself, as Oscar Wilde states through his character Basil Hallward:

“every portrait that is ever painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion.”

Richard Wendorf supports this view, he states because of the collaborative nature of the sitting, the work that is created is a portrait of the painter in that society, because of the way in which he has established his practice and constructed his studio. The relationship between Sandys’ and his sitters therefore could be seen as unimportant his portraits are instead a presentation of his own style and ideologies. William Hazlitt claims however the bond between painter and sitter is like the relationship of two lovers, focused on the same aims artist and sitter reinforce one another’s focuses and ardour, there is a conscious vanity in portraiture which Hazlitt claims to be the true elixir of human life Sandys’ sexual relationships with his sitters therefore becomes understandable. Whereas Hannah Westley states it is the temporal nature of painting that opens up the possibility of a relationship between artist and sitter it is charged with contradictory feelings and instincts like Hazlitt she claims it can also be an act of love, each partner gives himself without reserve. In some contexts however sitters are given president over the artist with the sitter being named in the title and the artist not being named for example in the Howell portrait by Sandys Howell’s full name is included but not Sandys’, Howell’s name is also on the left and as Westerners read from left to right this gives further prominence to the sitter.

It is evident from this study that Frederick Sandys when having a closer relationship with a sitter is able to explore his own styles and ideals further. The use of the Pre-Rephaelite archetype of the ‘femme fatales’ only transpires when Sandys has had a close physical relationship with the sitter seen in Medea, Morgan Le Fay and Love’s Shadow. When Sandys is instead a friend or acquaintance of the sitter the portraits become a lot less detailed (showing less of his own identity in the background) and more about the realistic depiction of an individual or an expression, which is seen in the Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell and Helen of Troy. Sandys’ relationship with his sitters therefore was pivotal to his creative process. The portraits explored in this study shows the individuality of the relationship Sandys had with each sitter; from sexual partner, to life partner and to just an acquaintance. Sandys’ identity to the sitter changed as greatly as the depictions of individuals created by Sandys.

Background and Style

Background and Style

Compared to the previous piece the colours used are much darker. The dark, almost dirty, colours used in this painting are not a traditional type of palette, for a portrait of a couple in love. The black silhouetted figures dominate the picture space greatly contrasting the white portrait behind. The connection between Hepworth and Nicholson is shown in their intertwined bodies, represented in such a way that it is difficult to decipher which arm is Hepworth’s or Nicholson’s.The lighter face could be interpreted as Nicholson’s soul or the energy between the two, as there is more fluidity to the lines and colour, making it seem more ethereal. Echoing the blue in the previous portrait, between Hepworth and Nicholson. In this painting the influence of artists like Picasso can be seen in the reduction of representative form, drawing on the style of Picasso’s 1920s portraits of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter

Compared to the previous piece the colours used are much darker. The dark, almost dirty, colours used in this painting are not a traditional type of palette, for a portrait of a couple in love. The black silhouetted figures dominate the picture space greatly contrasting the white portrait behind. The connection between Hepworth and Nicholson is shown in their intertwined bodies, represented in such a way that it is difficult to decipher which arm is Hepworth’s or Nicholson’s.The lighter face could be interpreted as Nicholson’s soul or the energy between the two, as there is more fluidity to the lines and colour, making it seem more ethereal. Echoing the blue in the previous portrait, between Hepworth and Nicholson. In this painting the influence of artists like Picasso can be seen in the reduction of representative form, drawing on the style of Picasso’s 1920s portraits of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter

Who was Isabella D’este?

Who was Isabella D’este?

Contrastingly Perugino’s ‘The Battle of Chastity and Lasciviousness’ has a dizzying depiction of a battle between virtue and vice (a theme that runs through all of the studiolo paintings) By close guidance of D’este, Perugino uses Greek mythological characters to represent the moral battle between love and lust. Pallas and Diana represent lust and are in battle with Venus and Cupid, representative of love. Mantegna masterfully presents his story with clear pockets of narrative, where as Perugino’s battle, although presenting confusion, is unsuccessful in producing a legible narrative. It could be argued that Perugino was tailoring his work to D’este’s studiolo by presenting a work that needed to be studied in detail, but in doing so the message becomes aesthetically confused and does not give a striking overall reaction. The viewer is left feeling uneasy as there is no resolution to the combat, with the battle still in process the moral that love conquers is not expressed and so the painting fails to present the crux of the narrative. Similarly Mantegna’s work, although seemingly presenting balance, is challenged by the appearance of Vulcan.

Contrastingly Perugino’s ‘The Battle of Chastity and Lasciviousness’ has a dizzying depiction of a battle between virtue and vice (a theme that runs through all of the studiolo paintings) By close guidance of D’este, Perugino uses Greek mythological characters to represent the moral battle between love and lust. Pallas and Diana represent lust and are in battle with Venus and Cupid, representative of love. Mantegna masterfully presents his story with clear pockets of narrative, where as Perugino’s battle, although presenting confusion, is unsuccessful in producing a legible narrative. It could be argued that Perugino was tailoring his work to D’este’s studiolo by presenting a work that needed to be studied in detail, but in doing so the message becomes aesthetically confused and does not give a striking overall reaction. The viewer is left feeling uneasy as there is no resolution to the combat, with the battle still in process the moral that love conquers is not expressed and so the painting fails to present the crux of the narrative. Similarly Mantegna’s work, although seemingly presenting balance, is challenged by the appearance of Vulcan.

From his portrait Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell (Fig.3) Howell may seem quite an unlikely character to be a part of the inner circle of the Pre-Raphaelites: a stuffy, lethargic, formal man. Howell was however well accepted by the group for a long period partially due to his upbringing and also because of his experiences of what became his new profession. Howell did however fall from grace with accusations of theft and deception, and before this portrait he had become unpopular in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Charles Howell was the son of a British drawing master and so Howell had some understanding of art from his father and in turn he was able to better appreciate the art world, from an artist’s perspective. He became known by the Rossetti brothers; they met in 1857 and because of his appreciation of the aesthetic world and his taste in art he became closer to the Pre-Raphaelites and the art movement during the period. Sandys also made Rossetti’s acquaintance in 1857, and this could go to explain why he was also seen as an outsider in Pre-Raphaelite circles by not being at the formation of the ideals but instead just as an artist with a similar style.

From his portrait Portrait of Charles Augustus Howell (Fig.3) Howell may seem quite an unlikely character to be a part of the inner circle of the Pre-Raphaelites: a stuffy, lethargic, formal man. Howell was however well accepted by the group for a long period partially due to his upbringing and also because of his experiences of what became his new profession. Howell did however fall from grace with accusations of theft and deception, and before this portrait he had become unpopular in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Charles Howell was the son of a British drawing master and so Howell had some understanding of art from his father and in turn he was able to better appreciate the art world, from an artist’s perspective. He became known by the Rossetti brothers; they met in 1857 and because of his appreciation of the aesthetic world and his taste in art he became closer to the Pre-Raphaelites and the art movement during the period. Sandys also made Rossetti’s acquaintance in 1857, and this could go to explain why he was also seen as an outsider in Pre-Raphaelite circles by not being at the formation of the ideals but instead just as an artist with a similar style.